40 literary terms you should know

Aphorism: Short, sweet little sayings expressing an idea or opinion are familiar to everyone — they just don’t always know the technical term for them. Dorothy Parker was a particularly adroit user of aphorisms.

Apostrophe: Beyond a term for daily punctuation, apostrophe also pulls audiences aside to address a person, place or thing currently not present. O, Shakespeare! Such a sterling example of apostrophe use!

Applicability: The venerable Lord of the Rings author J.R.R. Tolkien coined this term when badgered one too many times about whether or not his beloved fantasy series was supposed to be a World War II allegory. It wasn’t, but he thought readers could easily apply such an interpretation to the text without losing anything.

Bete noire: While not an exclusively literary term, many critics do use it to denote the idea of avoidance found in many narratives. Family dramas, for example, are almost obligated to involve some sort of elephant in the room.

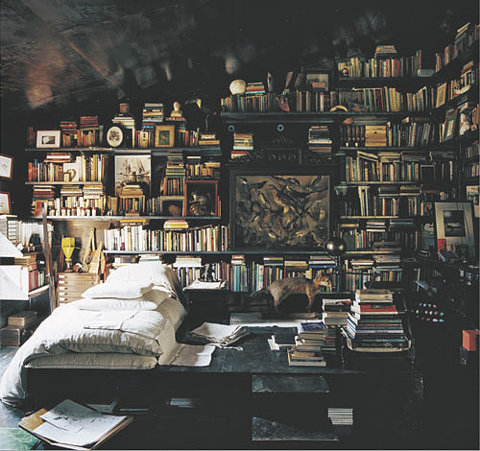

Bildungsroman: Coming-of-age stories, known as bildungsroman, are the warm, cozy socks of the literary world. Every writer has one, even though some are kind of gross and full of holes. For extra bibliophile points, try tossing out the term “kunstlerroman” when appropriate. That’s a special kind of bildungsroman following the growth of an artist or other creative type.

Bowdlerize: Because of his numerous silly cuts and edits to Shakespeare (SHAKESPEARE!), Thomas Bowdler has become immortalized as the unintentional founder of yet another word for censorship and needless meddling. When American The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy editions replaced the f-dash-dash-dash word with “Belgium,” it found itself on the receiving end of a serious bowdlerizing.

Byronic hero: Popularized by romantic poet Lord Byron’s life and works, this jaded, flawed hero archetype typically exhibits highly emotional, erratic, disrespectful and self-destructive behaviors isolating him or her from the rest of the world. Basically, Byronic heroes were emo before emo was a thing.

Caesura: Typically found in ancient Greek and Latin poetry, caesura represent pauses after a word, though not at the end or foot of a piece.

Death of the author: As hair-rippingly awful as Twilight may be, this literary phenomenon has absolutely nothing to do with clunking Stephenie Meyer’s head onto a pike for her egregious crimes against books (which would be absurd and rather mean). Rather, it stems from Roland Barthes’ argument that an author’s ideologies and life story have little to no bearing on a textual interpretation.

Denouement: The denouement occurs shortly after a story’s climax, but before its end. This serves to wrap up any dangly bits the author wishes to resolve.

Didactic: Everyone knows didactic literature, even if they don’t know the fancy term. It takes on an academic tone meant to educate, carrying with it connotations of heavy-handedness.

Epigraph: Many writers like to include quotes or passages at the beginning of their works to reflect the overarching theme or message. Mark Twain and his warning about shooting anyone wanting to critically analyze Huckleberry Finn (oops) famously parodied this trope. Iron Chef’s use of a George Bernard Shaw quote before each episode is a notable non-literary example. Allez cuisine!

Epistolary: Frankenstein, The Perks of Being a Wallflower and The Color Purple may have little in common on the surface, but they all share epistolary structure. Most or all of the narrative comes to readers through letters or other correspondence rather than a more traditional storytelling manner.

Fin de siecle: Put away the Ramones album and pick up some Oscar Wilde for a fin de siecle fix. Meaning “end of the century,” this phrase refers to creative works completed towards the end of the 1800s, reflecting Europe’s social and political mores.

Foil: Foils are characters meant to play off one another’s tics and quirks, like Leopold Bloom and Stephen Daedalus in Ulysses or Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson. Or Batman and Robin.

Hamartia: Aristotle coined this word to describe tragedies, particularly those brought about by an aristocrat’s ego, gluttony or silly mistake rather than outright sin.

Heresy of paraphrase: New Critic Cleanth Brooks believes in the impossibility of discerning meaning in poetry, and that it’s entirely possible to just enjoy its mere existence at a specific point in space and time.

Hubris: Hubris, or raging ego with a heaping helping of overestimation on the side, oftentimes brings about hamartia — and not always in Greek drama!

Humours: Ancient Greeks and Romans believed the human body to be comprised of four humours — blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm — that corresponded with different personality types, seasons, organs and elements. It’s pretty much accepted as complete scientific doodie by now, but the concept has left an indelible impression on literary history all the same.

In medias res: More than literary narratives use the in medias res device, which drops audiences straight into the middle of the action and builds upon the recent past as the tale unfolds.

Intertextuality: Literary critics comparing different works to one another, especially as they relate to retellings and references, practice intertextuality — as do the writers using the device. Adapting religious or traditional stories remains popular in almost every nation’s canon.

Irony: It’s not about rain on wedding days, free rides after payment or 10,000 spoons when a knife is needed. Look at it as a situation where the outside and the inside exist in a dissonant state, though there exists a couple other interpretations Read O. Henry’s short story “The Gift of the Magi” for a particularly bittersweet, memorable depiction of irony.

Literary agent hypothesis: Bookworms with a postmodern bent will find the literary agent hypothesis fascinating. It posits that authors of fiction serve as “literary agents” to real events, changing around the reality to make for a more compelling narrative. Like the philosophy from which it stems, this critique style enjoys playing around with the nature of the known and unknown world.

Magic realism: Like the best surrealist paintings, magic realism blends the wholly terrestrial with the wholly oneiric to form one frightfully beautiful, emotional atmosphere. Anyone fortunate enough to have read Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel will know exactly how much it can punctuate a novel and make it something memorable and special.

Malapropism: When used properly, deliberately replacing words with different ones (usually homophones) can really make a humorous scene pop. This technique comes from the character Mrs. Malaprop, created by Richard Brinsley Sheridan for his play The Rivals, whose verbal quirks reflected such things.

Meiosis: Satirical works, particularly those hailing from Britain, will oftentimes use understatement to greatly hilarious effect. Impress or (more likely) annoy book club friends by using the technical term “meiosis” instead.

Meta: Though meta as a word and a prefix usually means an abstract offshoot of a concept, many critics today use it to mean a self-referential text. This list is meta because it’s aware of its list status. Also, it’s kind of scared of this newfound awareness, and its lack of maturity may cause a lashing out at those trying to help. Please teach it to love.

Mise en scene: While mostly used in cinema or theatre critique, literary aficionados can still (and often do) use “mise en scene” to describe the setting, mood and atmosphere of a text.

Picaresque: Swashbucking adventure stories with a scrappy, ne’er-do-well scamp of a protagonist are a beloved narrative staple. Known as “picaresques,” they’ve heavily influenced a diverse selection of authors and spawned some of the world’s most lauded works.

Purple prose: Authors oft-utilizing egregiously eloquent, ornate prose possessed of sterling caliber and astronomical romanticism may indubitably find themselves indicted for their “purple prose.” There’s a time and a place for eloquence and SAT words, but it definitely isn’t every time and every place. Any text referring to eyes as “orbs” without any sort of irony is automatically guilty of this linguistic sometimes-offense. No matter what. No exceptions. Also, every romance novel ever written. Even if a long-lost manuscript attributed to Bukowski ever materialized and proved a romance novel, it would still be made of purple prose.

Roman a clef: Real-life figures and adventures oftentimes end up thinly and not-so-thinly appearing as fiction in a device critics like to call roman a clef because it sounds fancy and stuff. Hundreds of examples exist, but some of the most popular can be found in Jack Kerouac’s oeuvre.

Scene a faire: Not all scenes a faire are always cliche, but all cliches are scenes a faire. This critical phrase refers to idioms and tropes audiences expect of a narrative and authors feel obliged to provide, particularly when it comes to genre fare.

Sobriquet: Sobriquets are nicknames almost everybody knows when they encounter them in speech or text, such as “The Big Apple” for New York City, where every American novel ever written takes place. Even the ones set in Texas.

Syllogism: Rhetoric buffs amongst the bookworm set need to know the definition of syllogism, lest the Ghost of Aristotle arise and get its poltergeist on. It involves a 3-part deductive, logical reasoning structure comprised of the major premise, minor premise and conclusion.

Synecdoche: When readers encounter a part meant to represent a whole, they’ve come face to face with the synecdoche who sold the world. Moby Dick’s iconic albino tail, for example, symbolizes the entire cetacean.

Tranche de vie: Use “tranche de vie” in place of “slice of life” to sound all sophisticated and French when discussing Raymond Carver’s Cathedral.

Trope: Tropes actually have a few definitions, but are frequently used to refer to familiar literary devices, events and archetypes. A great many of the vocabulary words listed here, for instance. They can also be metaphors or other types of figurative language.

Ubi sunt: At some point in their lives, everyone reads a literary work (or its corresponding Cliffs Notes) about the transience of mortality and how people are really just ants, man, ants in this big cosmic soup. At some point in their lives, everyone reads an ubi sunt, they just didn’t know there was a Latin phrase for it because that language is dead.

Unreliable narrator: Humbert Humbert, that scumbag around whom Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, is one of literature’s most notable unreliable narrators. Readers can’t exactly trust everything these speakers say as what exactly transpired, especially since they usually only get one side of the story. Try layering an unreliable narrator on top of the literary agent hypothesis for hours of mind-bending metaedutainment!

Verisimilitude: An easy way to remember “verisimilitude” involves noting that unreliable narrators don’t practice it.

Found at OnlineClasses.com