With this blog post, three things are going to happen. First, as a history teacher it will open up vast stores of media you didn’t think had any use in teaching history. This is important, because there isn’t a lot of news video of the Revolutionary War. Second, it will make you one of the most powerful visual creators and communicators in your building. And third, (and I’m sorry about this) you’ll probably stop watching television for entertainment, except in small bursts, in about three weeks time.

Before I became a teacher 7 years ago, I was a different person. A television producer and writer. Life’s funny that way. I worked for NBC, CNN, Associated Press Television News and other organizations. I would like to pass along a big secret, the hidden gem, the under-the-table truth on how to produce eye-popping, emotion-grabbing, communicative media. It’s the Visual Metaphor.

Easier to explain than to do, the Visual Metaphor makes up most good media.

DEFINITIONS:

A metaphor is:

1. A figure of speech in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable.

2. A thing regarded as representative or symbolic of something else, esp. something abstract.

( source: http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/metaphor )

In the vernacular of the peasantry, a metaphor is “comparing two things without using like or as.”

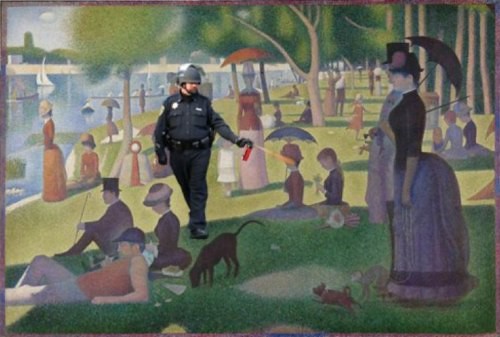

A Visual Metaphor simply replaces the words for one of the two things compared, with a picture or video.

IMPLEMENTATION:

When using metaphors for teaching, we choose two things, one is something our students know (prior knowledge), the second is some concept we are trying to teach. The second is usually not “literally applicable” and is usually “something abstract” as noted in our definitions above. When creating a Visual Metaphor, one wants to use the visual piece to communicate the second, abstract, something.

Watch this video:

Uncontacted Amazon Tribe: First ever aerial footage from Survival International on Vimeo.

We see here long-bows, longhouses, and any number of artifacts we are trying to teach children about in K-5 environment. We have standards to cover about Native Americans which are contained in this video. Of course the video is not about Native North Americans. It’s about Native South Americans and was shot this year.

What is an underlying theme in the video is the uncontacted tribe‘s reaction to seeing the plane. They are scared.

OK, that was pretty easy, let’s try another:

When teaching slavery, we have limited visuals with which to work and the subject is both disturbing and difficult. This video compares slavery to a cattle auction. Every kid who’s been to a county fair knows what a cattle auction looks like. They’ve seen the pen. The video is talking about modern slavery, not the period in U.S. history 100 years ago.

Clearly both these videos are not proper for some groups of students and even the cattle market would need to be stopped at the high school level before the last bit about the modern sex slave trade.

But what is critical is both of these videos speak to the emotion of the participants in similar situations. Universal emotional truths. People caught up in a trade as slaves would have certain emotional reactions and it isn’t too much of a stretch to paint the picture. Since we are using these videos as metaphors, we aren’t saying this is exactly how the African slaves felt when they were brought to North America. Nor are we saying this is exactly how the Native Americans might have felt when they encountered european settlers. However it’s important for getting information across.

People use the framework of emotions to organize information, at the gut level. They use emotional intelligence as a wire frame on which to hang facts and figures. It’s what drives most media. It’s the most difficult piece to bring to teaching history — making it real on the gut level. Great history teachers have been able to do this. My favorite history teacher did.

So much of the traditional teaching of history is the accumulation of facts. The parsing and organization of huge amounts of empty data. It’s the stellar history teachers that make it all come alive. It’s not a big secret, they speak to the emotional intelligence, and use that as a scaffold on which to organize the data.

Neither of these two videos are mock-ups. Neither of them are “infotainment” with the types of historical inaccuracies inherent in using sources like Disney movies or Williamsburg to teach facts about history. As Visual Metaphors, it’s made clear they are not representations of historical fact. What they communicate is the gestalt of the historical issue. They are great writing prompts and discussion starters that allow students to place historical issues and the facts that surround them in an emotional context, without a lot of words and analysis. The information is transferred quickly and visually at an emotional level, and the syntheses comes from analyzing and working with the information.

Conversely, what torments many students in history class is the lack of context from the start. It is only at the end of a unit, when a diorama is complete and can be studied, that the gestalt of the historical issues are internalized. Syntheses is rarely achieved in such circumstances.

Using Visual Metaphors at the beginning, to provide context for the facts and figures, short circuits this teaching challenge.

FINDING VISUAL METAPHORS:

There are many sources of video, audio and still pictures: Discovery Education, YouTube.com, Creative Commons. All of these online sources have key word search.

Here’s the trick. When searching for visuals, don’t search using nouns (common or proper) for the actual thing you seek to teach. Search using adjectives, for the attributes of what you seek. You’ll find a hugh array of metaphorical options.

Find a storage place for your good visual metaphors. They hold over time.

SEEING VISUAL METAPHORS:

I said after reading this, you’ll probably stop watching television for entertainment. What happens (to people who work in television) is they start recognizing the use of Visual Metaphor. In every commercial, drama and movie, you’ll start to deconstruct the production process. And that’s, unfortunately, a side effect of becoming aware of this phenomenon in media.